International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Developmental Research

Application of the Gradient Descent Method for Optimization of Spin System Parameters of Metabolite Molecules by NMR Spectra

Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Dolgoprudny 141701, Russian Federation

Author and article information

Cite this as

Fattakhov MM, et al. Application of the Gradient Descent Method for Optimization of Spin System Parameters of Metabolite Molecules by NMR Spectra. Int J Pharm Sci Dev Res. 2026; 12(1): 001-008. Available from: 10.17352/ijpsdr.000058

Copyright License

© 2026 Fattakhov MM, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy is an effective physical method for metabolite fingerprinting, which involves the simultaneous and extensive analysis of a wide variety of compounds. The main disadvantage of the method, which hinders the progress of NMR metabolomics, is the need for manual processing of complex NMR spectra of biological samples. To automate the identification of metabolites in spectra, it is necessary to determine the parameters of the spin system of the main metabolites found in the samples under study. To address this issue, we propose an optimization algorithm that autonomously optimizes all relevant spin system parameters. The algorithm’s successful operation has been demonstrated on molecules of the most common amino acids found in NMR spectra of biological samples. The developed algorithm produced a proline spin-spin coupling matrix that, when evaluated by the Intersection-over-Union metric, showed better consistency with five experimental NMR spectra than literature matrices.

Metabolomics is an omics technology that has broad applications across various scientific fields and systems biology. The study of metabolic profiles involves the measurement and analysis of metabolites, including amino acids, carbohydrates, and lipids derived from biofluids, plants, and cellular extracts. It has been utilized to diagnose illnesses [1-3], explore disease pathology [4], examine host-parasite interactions [5] and monitor dietary impacts [6]. The significance of metabolomics in drug discovery and disease diagnosis lies in its ability to reflect direct changes in cellular activity through alterations in the metabolome.

The use of NMR (Nuclear Magnetic Resonance) in metabolomics and metabolic profiling is expanding rapidly, alongside advances in methods for measuring, analyzing, and interpreting complex datasets [7-15]. Metabolomics, also referred to as metabonomics, encompasses a comprehensive set of measurements on biological samples aimed at quantifying as many metabolites as possible and assessing changes in metabolite levels in response to external factors. In contrast, metabolic profiling focuses on a narrower range of metabolites, often tracking specific pathways. NMR is particularly effective for metabolite fingerprinting, which involves the simultaneous and extensive analysis of a wide variety of compounds [16].

Many programs have been developed to analyze the composition of metabolites using NMR spectra of biological fluids under study [17,18,20]. Nevertheless, the main tool currently used is the ChenomX program, in which the search for signals of metabolites in each spectrum is carried out manually ChenomX publications. Manual search for metabolites in the spectrum significantly slows down the analysis process and is a source of errors in the data. Automating the search for metabolites in the spectra is difficult because NMR spectra often have a complex structure. Moreover, the specific type of the metabolite spectrum may vary depending on the composition of the entire sample [21]. The exact structure of the NMR spectrum is determined by the matrix of the spin system, which contains the values of the chemical shift and the spin-spin interaction constants between all 1H nuclei. The authors [18] have developed the GISSMO package and a library of matrices of spin systems of metabolites. However, the calculation of the parameters of spin systems in the GISSMO package is carried out mainly manually, with the possibility of automatic optimization of each parameter separately.

For systems with a large number of nonequivalent spins, manual processing of spectra is often impractical. Even the simple task of determining the alignment signals requires an accurate estimation of spin-spin coupling constants in organic molecules, which cannot be achieved without a comprehensive analysis of the complex NMR spectrum. Typically, a set of peak positions and intensities in a reference spectrum serves as an identifier for the compound. However, these values can vary depending on external factors such as pH, temperature, and the strength of the magnetic field [22]. It is not possible to simply collect a set of parameters in the laboratory and further use them as a database for any cases. Thus, creating a tool that enables the calculation of system parameters without manual processing becomes crucial for more efficient spectrum analysis.

The analysis of chemical shifts and J-coupling constants is a valuable tool that enables the accurate determination of the parameters of the spin system. NMR spectral analysis involves solving a non-linear inverse problem, which is to determine the parameters (resonant frequencies and interaction constants) of a spin system that best matches experimental spectra. However, it is not always possible to guarantee the uniqueness of this solution, which makes it challenging to find the correct parameters. In particular, the challenge of identifying metabolites in human blood presents a significant difficulty, owing to their wide range of variability.

To address this challenge, optimization algorithms have been developed. These algorithms utilize synthetic spectrum generation and annealing simulations to analyze the shape of NMR spectral lines. In addition, specialized software packages such as GISSMO [18] assist in optimizing the spin system models on the algorithmic level. To advance methodological development, mechanical filtration can be effectively applied to metabolomics research. For further exploration, consider the works [19,23].

Materials and methods

Spectral form analysis

This work was conducted using equipment from the MIPT Shared Facilities Center. NMR spectra were acquired using a Varian Inova 500 NMR-spectrometer with a 1H Larmor frequency of 500 MHz. All experiments were conducted in liquid solutions, and the spin Hamiltonian of the molecule in this case can be represented as [24-27]:

H = HZ + HJ, (1)

where the first term represents the Zeeman interaction with the local magnetic field, while the second term represents the spin-spin J-coupling interaction:

Here, νk is the k-th spin precession frequency, and Jkl are J-coupling constants, which determine an interaction between the k-th and l-th spins. The precession frequency of the nuclear spin is determined as νk = γB0(1 − σk), where γ is the gyromagnetic ratio, B0 is the external magnetic field, and σk is the so-called shielding constant. Both resonant frequencies νk and coupling constants Jkl are the main characteristics of any molecule in NMR measurements and allow us to identify a specific molecule in a sample. One can consider the case of “weak” J-coupling between k-th and l-th nuclear spins: Jkl << |νk − νl|, when the corresponding part of the Hamiltonian can be reduced to the secular part: . Then the required calculations are simplified. However, for the case when Jkl is comparable to or greater than the chemical shift values difference |νk − νl|, which is also called “strong” coupling, it is necessary to consider the full contribution to the spin-spin interaction Hamiltonian without neglecting the non-secular part. Since “strong” coupling can be observed for some metabolites, we solved the optimization problem in a general way using a full form of Hamiltonian 3. Thus, the proposed algorithm does not rely on perturbation theory and considers “strong” spin-spin coupling (more general case), which makes computational methods more stable and allows us to successfully find parameters for, for example, AB systems.

Further, the corresponding matrix of the complete Hamiltonian (1) will be written in the basis of eigenstates of the Hamiltonian (2), that is, in the so-called computational basis. The eigenvalues of this matrix give us the energy levels of the nuclear spin system and, accordingly, the NMR spectrum, which depends on both chemical shifts and coupling constants. A comparison of the experimentally measured and calculated spectra gives us the opportunity to identify the corresponding molecule in the sample. In the following, the Hamiltonian matrix will be called the spin matrix.

All the necessary parameters of the spin matrices of molecules can be determined in experiments with pure samples, but in the studied samples containing both different concentrations of the molecules of interest and mixtures of molecules, these parameters may differ. Thus, we need to propose an efficient algorithm that modifies the parameters of the known spin matrix of a molecule in order to identify it from the observed NMR spectrum in the sample.

When creating the algorithm, it is necessary to take into account that the molecules interact with the environment, which leads to a broadening of the ideal lines of the observed spectra. In liquids, this broadening can be well described by the shape of Lorentz lines [28,29], which corresponds to the exponential relaxation law. In our model, we will use the law of exponential relaxation, which determines for each central line of the spectrum the corresponding width and shape of the line. We can represent the transformation of the observed NMR signal into the corresponding spectrum using the following relations:

where M(t) is the experimentally observed signal, w is the peak width (relaxation rate), and ν, ν0 – spin resonant frequency with and without shielding, θ(t) is the Heaviside function, F is the Fourier transform operation,, which allows for shifting from the time-domain signal (FID) to the frequency-domain (spectrum). Therefore, the Lorentz peak model is used to generate the spectrum, and we, together with the parameters of the spin Hamiltonian, also train the relaxation coefficients.

For the universality of the model, we will train chemical shifts δ rather than resonant frequencies ν, which are field dependent:

where νTMS is the resonant frequency for tetramethylsilane.

When acquiring NMR spectra, a large number of scans are usually accumulated and averaged. To speed up the registration of spectra, the time between scans is usually set to about 3-6 s. For some nuclei of a molecule, this time may be insufficient for complete longitudinal relaxation, which may lead to a decrease in the intensity of the signal of this nucleus in the averaged NMR spectrum. To account for this factor, we introduced the parameter r affecting the intensity of peaks.

Thus, it is easy to see that in order to solve the problem, we need to find the following optimal parameters and values: chemical shifts, the matrix of J-coupling constants, relaxation rates that determine the width of the lines, as well as parameters for correcting the intensity of the lines.

Model architecture

The optimization algorithm is organized as follows: it receives a spectrum, which is represented by the y-axis coordinates of a graph, as input. The goal is to find the optimal model parameters in order to generate a synthesized graph that most closely resembles the original spectrum being processed. For these reasons, it is convenient to represent the frequencies of the spectrum, relaxation rates, and correction parameters as the corresponding vectors and . The model will predict a set of system parameters and a matrix of coupling constants J using the experimental spectrum as input data.

In terms of meaning, it can be divided into two modules: internal and external. At the internal level, the model will build a synthetic spectrum from the current values of the system parameters. In turn, at the outer level, the model performs gradient optimization of the system parameters by comparing the experimental data (input) with the synthetic spectrum obtained from the inner level. In our work, we will apply the optimization algorithm only to data from 1H spectra. But algorithm principles can be easily applied to study isotope spectra with other resonant frequencies, for example, 19F or 13C.

To build synthetic spectra for given parameters, we calculate the Hamiltonian of the system, determine its eigenvalues, select possible transitions using selection rules, and construct overall spectra by superimposing Lorentzian broadening on corresponding frequencies.

Optimization challenges

The model is implemented using the PyTorch machine learning framework for the Python programming language. This design ensures that the entire model is fully differentiable, allowing end-to-end optimization via gradient descent. The integration of physics-based computations (e.g., Hamiltonian construction and eigendecomposition) with conventional deep learning techniques facilitates the accurate simulation of complex spectral patterns, while also enabling parameter optimization based on experimental data.

To formulate an optimization problem for our model, we chose a loss function in the form

which is often used to process the Fourier spectra of various signals. Here, ysim, yexp — graphs of the corresponding synthetic (generated) and experimental (ground truth) spectra. This loss function was chosen for optimization because of the following reasons. First, in NMR spectroscopy, spectra are often processed in the frequency domain (Fourier space), where the norm of the vector corresponds to the intensity of the radiation. Cosine similarity measures the angle between spectral vectors in a multidimensional space, which physically corresponds to the degree of spectral similarity, regardless of the absolute amplitude, which depends on the strong magnetic field magnitude used for measurement. Second, the logarithmic transformation serves to numerically stabilize and prevent getting stuck in deep local minima (as discussed in the context of Figure 1). Finally, in the loss function (6) shift by 2 is due to the numerical stability of calculations. Generally, we do not know of a generally accepted loss function for solving such problems. Of course, it is possible to use other loss functions, for example, Mean Squared Error (MSE), Mean Absolute Error (MAE), or something else, but this requires a separate study and is already of special interest for research in the field of neural networks. General principles of hyperparameter selection for gradient optimization can be found in machine learning works [31-33].

To evaluate the quality of the chosen parameters, we will utilize IoU (Intersection-over-Union) as a metric because of its favorable interpretability. It can be perceived as the ratio of the intersection area to the area of the union of the experimental graph and the graph drawn by our model. In the context of the identification of metabolites, this corresponds to the criterion: “what proportion of the informative spectral region coincides between the two spectra”. Also, this metric has invariant properties to baseline shifts and uneven amplitude changes. Note that experimental spectra are subject to measurement errors, which lead to underestimated results when using this metric.

The optimization problem arises due to narrow peaks, when incorrectly selected initial parameters can lead to a significant mismatch between experimental and generated peaks. For example, if the right peak of one doublet merges with the left peak of another, as shown in Figure 1, the optimization algorithm may fall into the trap of a local minimum. To solve this problem, we broadened the peaks of the experimental spectrum using convolution with a Lorentzian kernel.

Although the suggested gradient descent method does not offer a ready-made universal methodology, it can be used to optimize the parameters of spin systems instead of manually selecting parameters. Initial conditions of estimated values (chemical shifts, spin-spin interaction constants) are selected manually or from known sources [18](for example, GISSMO [18]). In the future, the parameters are optimized using the gradient descent method using a given loss function. After reaching the minimum of the loss function, a visual comparison of the model spectrum is performed, and the IoU is calculated to evaluate the optimization quality.

Results and discussion

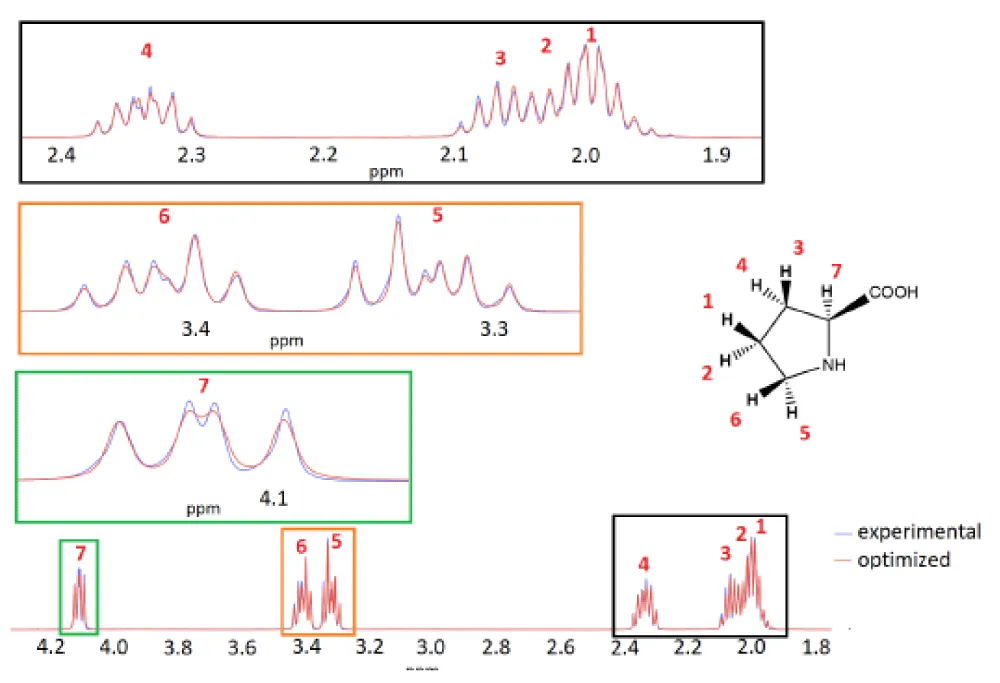

To illustrate the effectiveness of the model, we used the L-proline molecule as an example. The structure and 1H NMR spectrum of the L-proline molecule are shown in Figure 2. 1H NMR spectrum of L-proline contains signals from seven non-equivalent 1H nuclei. Most nuclei couple with several other nuclei at once, making the spectrum quite complex.

To a first approximation, the J-coupling constants do not depend on the external magnetic field, but under certain conditions, they may depend on pH and temperature. Most of the system parameters ( ) can vary depending on external factors such as pH, temperature, the strength, or inhomogeneity of the magnetic field [23]. At the same time, we will assume that the J-coupling parameters should not change significantly.

We will use the spin matrix provided by the ChenomX library for proline to find out if the parameters of our spin system can be improved. To do this, we will keep a fixed spin-spin coupling matrix J and try to optimize the remaining parameters by changing only the values of chemical shift δ and peak width w. Similarly, let’s look at optimization with additional fixed parameters of the effective peak intensity coefficient r and a system in which we optimize all parameters. We will evaluate the quality using the indicator we entered.

To assess the validity of such an assumption, five different L-proline spectra were analyzed:

- Spectrum acquired at 500 MHz on our spectrometer. The sample was dissolved in D2O, and a single-pulse pulse sequence was applied;

- Spectrum acquired at 500 MHz on our spectrometer. The sample was dissolved in phosphate buffer solution with pH 7.4, and a CPMG pulse sequence was applied.

- Spectrum acquired at 500 MHz obtained from the GISSMO open library.

- Spectrum acquired at 600 MHz obtained from the GISSMO open library.

- Spectrum acquired at 600 MHz obtained from the HMDB open library.

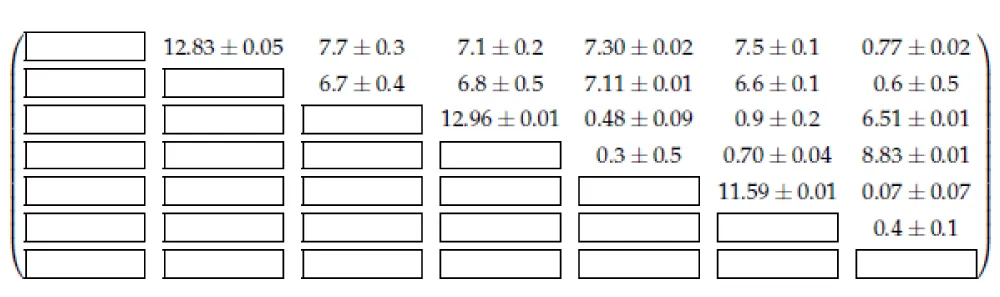

Due to the complexity of the task and the presence of noise in the real spectra, the models converge to slightly different spin matrices. Therefore, to get an approximate matrix, we use matrix averaging over all models. The average matrix is shown in Figure 3.

The IoU metrics obtained for the average J matrix are shown in Table 1, where the second column is responsible for the metrics with our average spin matrix. For a more precise verification of the dependence of the matrix J on the external parameters of the experiment, it is necessary to conduct a separate study; however, the data presented in the table indicate that this assumption is valid for the studied spectra.

Using our model and average matrix J, we have successfully optimized spin-system parameters for L-proline (Table 2 and Figure 2). To estimate the computational time required for the proposed method, optimization runs were performed on a laptop equipped with an NVIDIA GeForce GTX 1650 (mobile) graphics processing unit (GPU) and an Intel Core i5-10300H central processing unit (CPU) with 4 cores and 8 threads, and a base frequency of 2.5 GHz. The estimated computational time is about 10 minutes. The Adam, standard optimization algorithm, was used with a learning rate parameter configured at approximately 10−2. Furthermore, a ReduceLROnPlateau learning rate scheduler was implemented, which was parameterized with a factor of 0.9 to dynamically adjust the learning rate during the training process. In specific cases, the Lorentz expansion method was applied, typically utilizing values within the range of 1 to 10, in order to improve the robustness and stability of the optimization procedure. The code and associated data used in this study are openly available in the GitHub repository.

The article [30] presents the matrix J for the proline molecule obtained by annealing. Table 1: Calculated IoU for the full optimized spectrum and fixed averaged J matrix of the spin system for five different experimental spectra of L-proline algorhythm. In addition, another matrix J is available in the ChenomX application. To compare the matrices J from the above matrix sources with the matrix obtained using our algorithm, an optimization of the parameters of the spin system ( ) of proline was performed with a fixed matrix J obtained from each source of proline and all values r = 1.

Table 3 represents the metrics for the studied spectra. The first column is responsible for the metric of the model when optimizing all parameters. In other columns, ‘fix J and r’ corresponds to the optimization when we take the initial approximation matrix from [30] and ChenomX as the matrix J. In turn, ‘fix r’ represents optimization without using cor-rection factors⃗r.

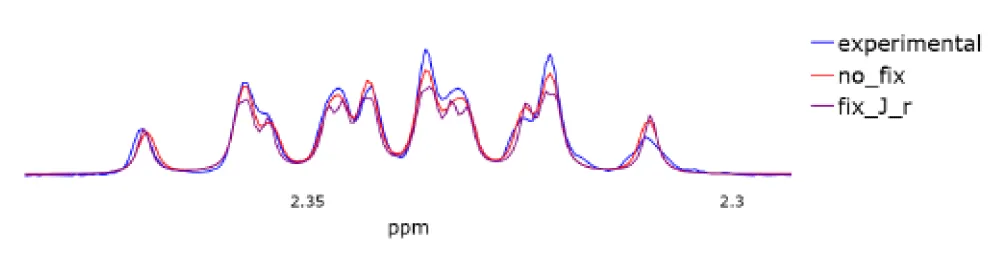

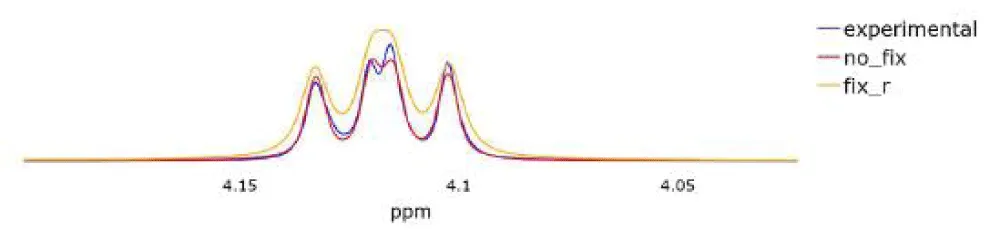

For clarity, we will also attach the graphs we have obtained. The graphs in Figure 4 illustrate the experimental spectrum, the spectrum calculated based on the spin system using ChenomX (designated “fix J r”), and the spectrum obtained from a fully optimized Table 3: Comparison of IoU for different spectra of proline model that includes interaction constants and correction factors (designated “no fix”). In Figure 5, it can be seen that the use of relaxation rates significantly improves the accuracy of the spectrum reconstruction. Figure 4 demonstrates how the model effectively handles complex peak features.

Based on the metrics, it can be seen that our model finds the parameters of the spin system more efficiently than the search using the annealing algorithm.

To illustrate how the algorithm works, we tested its performance on molecules of the most common amino acids found in NMR spectra of biological fluids. For this purpose, we uploaded experimental 1H NMR spectra and spin system matrices for these spectra from the GISSMO library. Then we calculated the IoU metric on the experimental spectra for fully optimized systems and on spin system matrices downloaded from GISSMO. The results of the comparison are shown in Table 4.

As can be seen from the table, IoU metrics calculated using our optimized spin-system parameters are more than metrics calculated using J matrices from GISSMO for all studied spectra. Due to the presence of noise, impurities, and asymmetry caused by nonuniformity of the constant magnetic field in the real spectra, all calculated metrics are less than 1. Nevertheless, most of the metrics calculated for optimized parameters are more than 0.9. The lowest IoU value was obtained for the spectrum of glycine, which contains only one peak (see GISSMO); therefore, solving the optimization problem here is generally unnecessary. Thus, our proposed algorithm allows us to effectively optimize the matrices of spin systems and produce better results than manual optimization.

For a further justification of the loss function and metric used, the estimated spectra obtained in the optimization modes indicated above (i.e. ”Full optimization”, ”fix J”, ”Fix J and r”, ”Fix r” like it was used in Table 3) are also compared with the ground-truth data in terms of classic loss functions MSE, MAE, RMSD. The spectrum of the ProlineGISSMO-499.84MHz-bmse000047 metabolite was used for comparison. Table 5 presents the comparison results. It can be seen from the results obtained that optimizing the parameters of the spin system in terms of the selected loss function 6 also improves quality in terms of classical loss functions (which, with precision to the sign, can also be considered as quality metrics in this context). The result obtained justifies the use of the selected loss function.

Conclusion

The obtained data allow us to conclude that our method gives results better than known open-source solutions, while not requiring manual processing. IoU metrics calculated for spin system parameters optimized for five different NMR spectra of L-Proline demonstrate better results than for spin systems with fixed J obtained from [30] and ChenomX. In addition, we demonstrate better optimization of spin system parameters for the spectra of the most common amino acids available in the GISSMO [18] database. The obtained model and parameters of the spin systems of metabolite molecules can be used to automate the determination of metabolite concentrations in biological samples and significantly accelerate and simplify the analysis of samples in the field of NMR metabolomics.

Data availability

The code and associated data used in this study are openly available in the GitHub repository.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge our colleagues for fruitful discussion.

Author contributions

- Fattakhov M.M.: Data Curation, Investigation, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft;

- Safin D.R.: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Project Administration, Writing – Original Draft, Writing – Review & Editing;

- Fedorov D.A.: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – Original Draft;

- Khramov E.S.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software;

- Verevkin E.R.: Data Curation, Software, Writing – Review & Editing;

- Perepukhov A.M.: Conceptualization, Data Curation, Investigation, Project Administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – Review & Editing;

- Belousov Yu.M.: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Project Administration, Supervision, Writing – Review & Editing.

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

- Nagana Gowda GA, Raftery D. NMR metabolomics methods for investigating disease. Anal Chem. 2023;95(1):83–99. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.2c04606

- He L, Jiang B, Peng Y, Zhang X, Liu M. NMR-based methods for metabolites analysis. Anal Chem. 2025;97(10):5393–5406. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.4c06477

- Zhang X, Xia B, Zheng H, Ning J, Zhu Y, Shao X. Identification of characteristic metabolic panels for different stages of prostate cancer by 1H NMR-based metabolomics analysis. J Transl Med. 2022;20(1):275. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-022-03478-5

- Aderemi AV, Ayeleso AO, Oyedapo OO, Mukwevho E. Metabolomics: a scoping review of its role as a tool for disease biomarker discovery in selected non-communicable diseases. Metabolites. 2021;11(7):418. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo11070418

- Olszewski KL, Morrisey JM, Wilinski D, Burns JM, Vaidya AB, Rabinowitz JD. Host-parasite interactions revealed by Plasmodium falciparum metabolomics. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5(2):191–199. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2009.01.004

- Gu H, Chen H, Pan Z, Jackson AU, Talaty N, Xi B, et al. Monitoring diet effects via biofluids and their implications for metabolomics studies. Anal Chem. 2007;79:89–97. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/ac060946c

- Cobas C. NMR signal processing, prediction, and structure verification with machine learning techniques. Magn Reson Chem. 2020;58:512–519. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/mrc.4989

- Johnson CH, Gonzalez FJ. Challenges and opportunities of metabolomics. J Cell Physiol. 2012;227:2975–2981. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/jcp.24002

- Emwas AH, Roy R, McKay RT, Tenori L, Saccenti E, Gowda GAN, Raftery D, et al. NMR spectroscopy for metabolomics research. Metabolites. 2019;9:123. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/metabo9070123

- Wishart DS. Quantitative metabolomics using NMR. Trends Anal Chem. 2008;27:228–237. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2007.12.001

- Markley JL, Bruschweiler R, Edison AS, Eghbalnia HR, Powers R, Raftery D, et al. The future of NMR-based metabolomics. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2017;43:34–40. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copbio.2016.08.001

- Kumar D, Gupta A, Mandhani A, Sankhwar SN. NMR spectroscopy of filtered serum of prostate cancer: a new frontier in metabolomics. Prostate. 2016;76:1106–1119. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1002/pros.23198

- Feng C, Li H, Zhang C, Zhou Y, Zhang H, Zheng P, et al. Exploring the causal role of plasma metabolites and metabolite ratios in prostate cancer: a two-sample Mendelian randomization study. Front Mol Biosci. 2025;11:1406055. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2024.1406055

- Yagin FH, Gormez Y, Al-Hashem F, Ahmad I, Ahmad F, Ardigò LP. Biomarker discovery and development of prognostic prediction model using metabolomic panel in breast cancer patients: a hybrid methodology integrating machine learning and explainable artificial intelligence. Front Mol Biosci. 2024;11:1426964. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fmolb.2024.1426964

- Panach-Navarrete J, Gonzalez-Marrachelli V, Morales-Tatay JM, García-Morata F, Sales-Maicas MÁ, Monleón-Salvado D, et al. Urine metabolic analysis as a noninvasive method to diagnose prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2026;44(2):125.e1–125.e10. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urolonc.2025.10.015

- Martínez-Trevino SH, Uc-Cetina V, Fernandez-Herrera MA, Merino G. Prediction of natural product classes using machine learning and 13C NMR spectroscopic data. J Chem Inf Model. 2020;60:3376–3386. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00293

- Rohnisch HE, Eriksson J, Tran LV, Müllner E, Sandström C, Moazzami AA. Improved automated quantification algorithm (AQuA) and its application to NMR-based metabolomics of EDTA-containing plasma. Anal Chem. 2021;93:8729–8738. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c04233

- Dashti H, Westler WM, Tonelli M, Wedell JR, Markley JL, Eghbalnia HR. Spin system modeling of nuclear magnetic resonance spectra for applications in metabolomics and small molecule screening. Anal Chem. 2017;89:12201–12208. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.7b02884

- Tardivel PJC, Canlet C, Lefort G, Tremblay-Franco M, Debrauwer L, et al. ASICS: an automatic method for identification and quantification of metabolites in complex 1D 1H NMR spectra. Metabolomics. 2017;13:109. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11306-017-1244-5

- Atieh Z, Suhre K, Bensmail H. MetFlexo: an automated simulation of realistic 1H-NMR spectra. Procedia Comput Sci. 2013;18:1382–1391. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2013.05.305

- Bhinderwala F, Roth HE, Noel H, Feng D, Powers R. Chemical shift variations in common metabolites. J Magn Reson. 2022;345:107335. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2022.107335

- Bansal N, Kumar M, Gupta A. Richer than previously probed: an application of 1H NMR reveals one hundred metabolites using only fifty microliter serum. Biophys Chem. 2024;305:107153. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpc.2023.107153

- Gupta A, Kumar D. Beyond the limit of assignment of metabolites using minimal serum samples and 1H NMR spectroscopy with cross-validation by mass spectrometry. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 2018;151:356–364. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpba.2018.01.015

- Pople JA. The theory of chemical shifts in nuclear magnetic resonance. I. Induced current densities. Proc R Soc Lond A. 1957;239:541–549. Available from: https://royalsocietypublishing.org/rspa/article-abstract/239/1219/541/9990/The-theory-of-chemical-shifts-in-nuclear-magnetic?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- McConnell HM. Theory of nuclear magnetic shielding in molecules. I. Long-range dipolar shielding of protons. J Chem Phys. 1957;27:226–229. Available from: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1957JChPh..27..226M/abstract

- Ramsey NF, Purcell EM. Interactions between nuclear spins in molecules. Phys Rev. 1952;85:143–144. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRev.85.143

- Gutowsky HS, McCall DW. Nuclear magnetic resonance fine structure in liquids. Phys Rev. 1953;82:748–749. Available from: https://journals.aps.org/pr/abstract/10.1103/PhysRev.82.748

- Abragam A. The principles of nuclear magnetism. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1961. Available from: https://www.scribd.com/doc/75401377/Abragam-The-Principles-of-Nuclear-Magnetism

- Slichter CP. Principles of magnetic resonance. Springer Series in Solid-State Sciences. 1996. Available from: https://books.google.co.in/books/about/Principles_of_Magnetic_Resonance.html?id=zgnrRkaIhFoC&redir_esc=y

- Cheshkov DA, Sinitsyn DO, Sheberstov KF, Chertkov VA. Total lineshape analysis of high-resolution NMR spectra powered by simulated annealing. J Magn Reson. 2016;272:10–19. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmr.2016.08.012

- Murphy KP. Probabilistic machine learning: an introduction. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 2022. Available from: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262046824/probabilistic-machine-learning/

- Goodfellow I, Bengio Y, Courville A. Deep learning. Cambridge (MA): MIT Press; 2016. Available from: https://mitpress.mit.edu/9780262035613/deep-learning/

- Deisenroth MP, Faisal AA, Ong CS. Mathematics for machine learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2020. Available from: https://mml-book.github.io/book/mml-book.pdf

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley