International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Developmental Research

Long-term survival after Acute Ischemic Stroke by types of reperfusion therapy, sex and chronic treatments of cardiovascular conditions

José Luis Clua-Espuny1,2*, Sònia Abilleira3, Queralt-Tomas M Lluïsa1,2, González-Henares MA1,2, Muria-Subirats E1, Ballesta-Ors J1 and Gil-Guillen V Fco4

2University Institute for Primary Care Research (IDIAP) Jordi Gol, Barcelona, Spain

3Stroke Programme, Agency for Health Quality and Assessment of Catalonia, CIBER Epidemiología y Salud Pública (CIBERESP), Barcelona, Spain

4Chair in Family Medicine Miguel Hernandez University, Elche, Spain

Cite this as

Clua-Espuny JL, Abilleira S, Lluïsa QTM, González-Henares MA, Muria-Subirats E, et al. (2018) Long-term survival after Acute Ischemic Stroke by types of reperfusion therapy, sex and chronic treatments of cardiovascular conditions. International Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences and Developmental Research 4(1): 024-030. DOI: 10.17352/ijpsdr.000019Purpose: Compare long-term survival by sex after reperfusion therapies with simultaneous medical therapy of cardiovascular conditions.

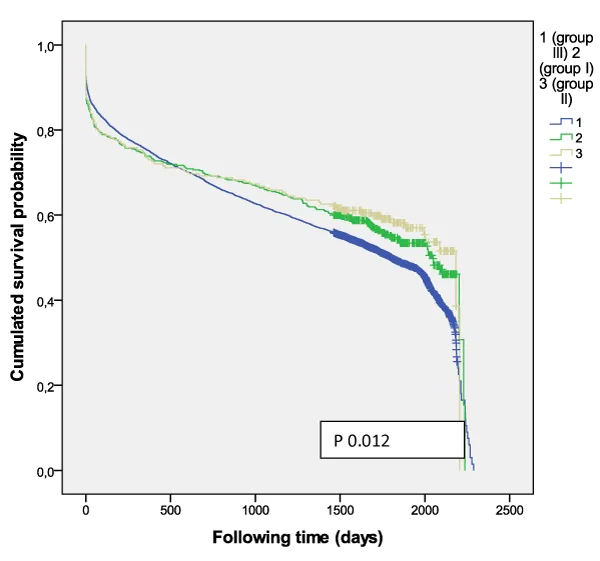

Methods: AIS patients identified from the population-based register between 01Jan2011 and 31Dec2012 and classified into: 1) AIS + intravenous thrombolysis [group I], 2) AIS + mechanical thrombectomy with or without intravenous thrombolysis [group II], and 3) AIS + medical therapy alone (no reperfusion therapies) [group III]. Follow-up went through up until December 2016. Statistical approaches were employed for analyzing survival outcomes and their relationship with reperfusion therapy.

Results: 14,368 AIS patients (men 50.1%), 77.1±11.0 years-old. There was higher survival among those treated with intravenous thrombolysis (p <0.001); women treated with thrombectomy (p <0.001); and women <80 year-old without reperfusion therapy. The most common medications were antiplatelets (52.8%), associated with lower survival (p<0.001); and statins (46.5%), associated with higher survival. The regression model produced the following independent outcome variables associated to mortality: anticoagulant HR 1.53 (CI95% 1.44-1.63, p<0.001), diuretics HR 1.71 (CI95% 1.63-1.79, p<0.001), antiplatelet HR 1.49 (CI95% 1.42-1.56, p<0.001), statins HR 0.73 (CI95% 0.70-0.77, p<0.001), A-IIRA HR 0.93 (CI95% 0.89-0.98, p=0.008) and reperfusion therapy HR 0.88 (CI95% 0.81-0.97, p=0.009).

Conclusions: Under 80 year-old the women had a better outcome than men when treated with thrombolysis therapy and/or catheter-based thrombectomy and with medical therapy alone. The men had a better outcome when received intravenous thrombolysis. The chronic cardiovascular pharmacotherapy must be evaluated to determine their effects on the reperfusion therapy outcome and whether they should be included as factors in the decision to reperfusion.

Long-term survival after Acute Ischemic Stroke by types of reperfusion therapy, sex and chronic treatments of cardiovascular conditions.

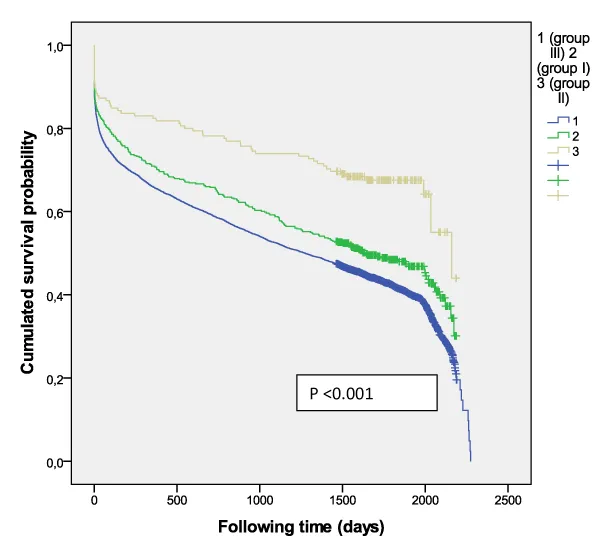

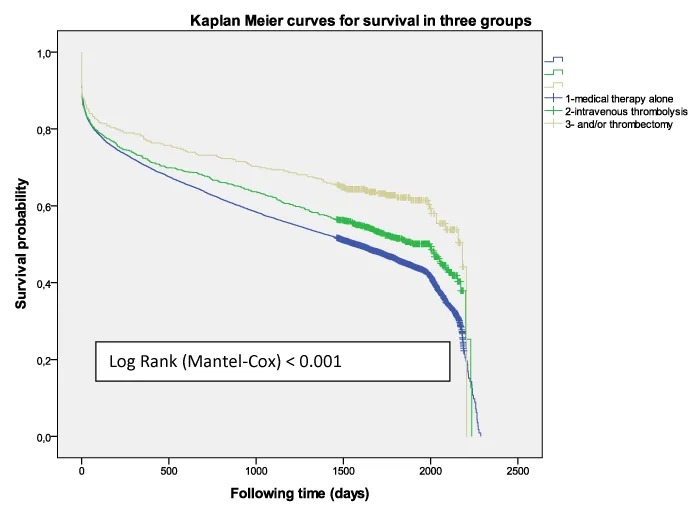

Long-term Survival differences after reperfusion therapy.

Background

A wide variety of factors influence stroke prognosis, including age, stroke severity and comorbid conditions [1-4]. In addition, interventions such as reperfusion therapy can play a major role in the outcome of ischaemic stroke. Previous reports [5-10], concerning sex differences in stroke [7,11,12] and outcome are inconsistent [13,14] and are sometimes difficult to interpret and the reasons for disparities remain unclear despite adjustment for baseline differences in age, prestroke function and comorbidities. Actually most current information about outcomes and safety is derived from patients at 3-12 months and mostly coming from the hospital activity that are not available in the area of primary care. There are neither studies assessing the efficacy of revascularization (medical therapy alone vs intravenous thrombolysis vs mechanical thrombectomy) in long-term outcome beyond hospital discharge, nor evaluation of potential effects on survival from interactions of cardiovascular chronic treatments and revascularization therapy associated with sex differences.

This work is a continuation and extension of the Ebrictus study [15-17]. The aim of our study was to evaluate outcomes after acute ischemic stroke (AIS) in a large national cohort to determine whether sex and drugs for management of chronic cardiovascular conditions are associated with long-term survival differences after revascularization.

Methods

Study design and setting

Data collection and study procedures: This cohort study is based on AIS patients identified from the Minimum Basic Data Register at hospital discharge (CMBD-HA) through specific ICD-9 diagnostic and procedure codes. Access to population-based data was reached through the Programa public d’Analítica de Dades per a la Recerca i la Innovació en Salut a Catalunya (PADRIS). Study period was from 01Jan2011 through 31Dec2012 in Catalonia, Spain. Eligible patients were between the ages of 15 and 90 years. The study protocol, which is available at Long survival after ischemic stroke and thrombolysis in Catalonia, ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03247036, and has been certified by the Independent Ethics Committee (CEI) of University Institute for Primary Care Research (IDIAP) Jordi Gol, code 4R17/017.

The primary outcome was all-causes mortality at 5 years, according to the external certified registry. The study complies with the Helsinki Declaration and the local ethics committee requirements for clinical research.

Case definition

The automated operation of the PADRIS database retrieved all patients with a diagnosis code of AIS (codes 433.x1, 434.xx, and 436) with and without any of the following procedures codes: 99.10 “Injection or infusion of thrombolytic agent”, 39.74 “Endovascular removal of obstruction from head and neck vessel(s)”, and 38.91 “Arterial catheterization”. According to ICD-9 procedure codes, the cohort was classified into: 1) AIS + intravenous thrombolysis [group I], 2) AIS + mechanical thrombectomy with or without intravenous thrombolysis [group II], and 3) AIS + medical therapy alone (no reperfusion therapies) [group III]. The total dose of thrombolytic agent was alteplase (0.9 mgr/kg not to exceed 90 mgr.) based on patient weight.

The variables collected included: date of hospital admission, date of discharge, age, sex, treatment group (I, II or III), medication dispensation from the Integral System of Electronic Prescription (SIRE) from at least three months before episode (anticoagulant, antiplatelets, statin, antidiabetics, diuretics, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, and beta-blocker); and patient vital status (alive/dead), and date (day/month/year) of death from the Central Register of people insured (RCA). All these registries are population-based and managed by the Health Department, Government of Catalonia.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was undertaken with the following: a) Descriptive study of basic statistics and standard deviation of key variables stratified by age and sex; b) The probability of survival was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, and the hazard ratio (HR) was obtained by using the Cox proportional hazard regression model. Mortality was interpreted as overall mortality. The variables were included in a multivariate model performed with adjustment for age, sex, and type of medication. The analysis and processing of data were performed using the SPSS 11.5 statistical package for Windows.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

A total of 14,368 AIS patients were included (men 50.1%). Table 1 shows the baseline demographics and cardiovascular medication used. The average patient age was 77.1±11.0 years and average follow-up was 3.1±2.2 years. Men (74.2±11.1) were significantly younger (p<0.001) than women (80.0±10.2). The most commonly medications were antiplatelets (52.8%) associated with lower survival outcome (p<0.001), and statins (46.5%), associated with higher survival outcome, independent of sex. Between the ages of 60 and 79 years, the most prescribed medications included anticoagulants (13.5-15.3%), antidiabetics (34-37.6%), statins (54.5-55.7%), diuretics (54.8%) and antiplatelets prescriptions which increased progressively from 44.4% at <60 years to 63.4% at >90 years.

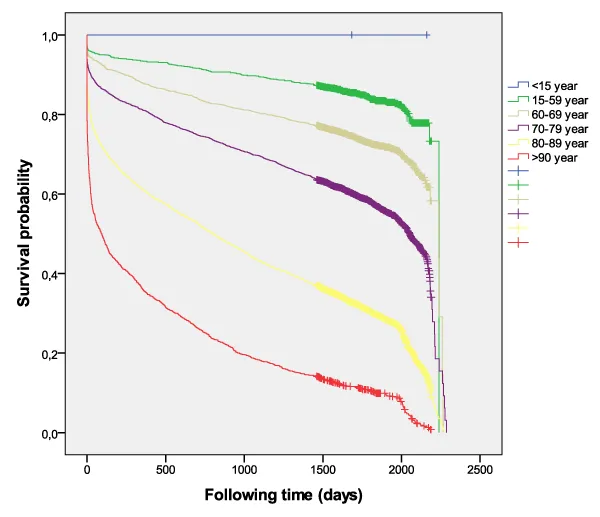

Mortality rates

Overall, all-causes mortality was 43.8%, increasing from 17.1% <60 years up to 93.5% >90 years (Figure 1). The cumulative 5-year survival proportion was 0.30±0.06 among women and 0.38±0.02 among men (p<0.001) after stroke. The regression model produced the following independent outcome variables: anticoagulant HR 1.53 (CI95% 1.44-1.63, p<0.001), diuretics HR 1.71 (CI95% 1.63-1.79, p<0.001), antiplatelets HR 1.49 (CI95% 1.42-1.56, p<0.001), statins HR 0.73 (CI95% 0.70-0.77, p<0.001), A-IIRA HR 0.93 (CI95% 0.89-0.98, p=0.008) and reperfusion therapy HR 0.88 (CI95% 0.81-0.97, p=0.009).

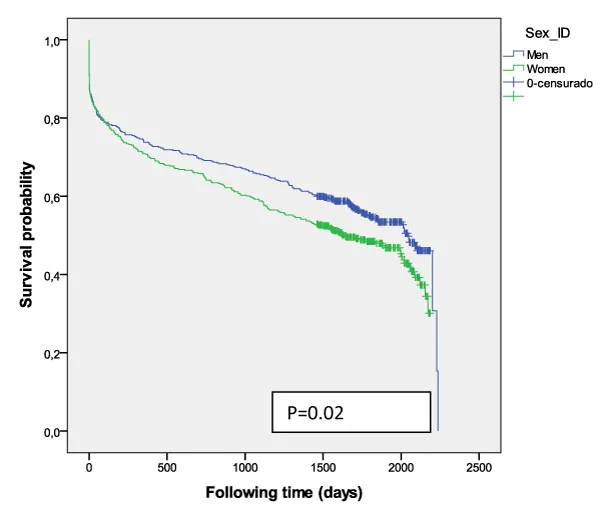

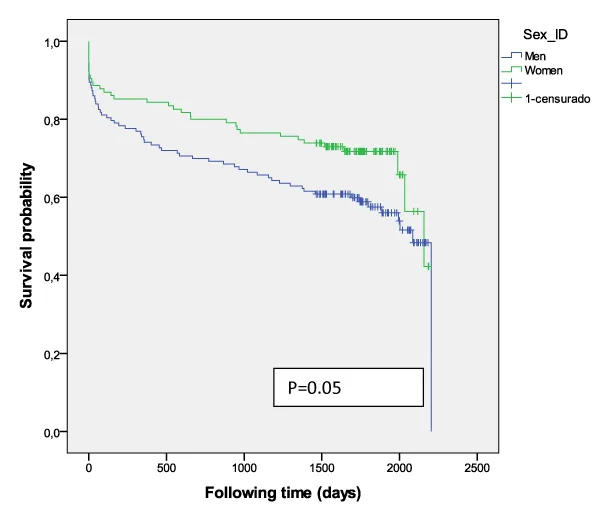

941 patients (471 women) received intravenous thrombolysis [group I] and had better survival than those who did not receive it (p =0.001) with an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) 0.83, [0.764-0.913] at 5-year survival, higher among men (p=0.02) (Figure 2). Women were older than men (78.4±8.2 vs 73.4±10.0, p<0.001). A higher mortality was shown among those treated with diuretics (p<0.001) and/or antiplatelets (p =0.001) independent of sex. The multivariate regression model identified the following independent outcome variables: age HR 1.08 (CI95% 1.06-1.09, p=0.001), diuretics HR 1.34 (CI95% 1.12-1.61, p<0.001), antiplatelets HR 1.34 (CI95% 1.12-1.60, p<0.001), anticoagulant HR 1.43 (CI95% 1.03-2.00, p=0.03) and antidiabetics HR 1.24 (CI95% 1.02-1.52, p=0.03). Of the 376 cases who were treated with thrombolysis therapy and/or catheter-based thrombectomy [group II] the number was significantly higher among men (p=0.01), but resulted in better survival outcomes among women (p=0.05) (Figure 3) than men, and got the best survival profile among women (p <0.001) (Figures 4,5).

13,051 (90.8% patients, women 50.0%) were treated with medical therapy alone [group III]. They were significantly older than those with reperfusion therapy (77.4±11.1 vs 75.9±9.5, p<0.001), and women were significantly older than men (p<0.001) (80.3±10.1 vs 74.4±11.1). Overall, there was higher survival (p<0.001) among women under 80 years. The overall survival probability was 0.29±0.08 among women and 0.37±0.06 among men (p<0.001) 5 years after stroke. Mortality was higher among those treated with anticoagulants (p<0.001), diuretics (p<0.001), antiplatelets (p<0.001) and beta-blockers (p=0.02); but the survival was significantly longer if patients were treated with A-IIRA (p<0.001), antidiabetics (p<0.001) and statins (p<0.001) without differences by sex. The beta-blockers benefited only women and the antidiabetics benefited only men (p<0.001). The multivariate regression model identified the following independent outcome variables: A-IIRA HR 0.89 (CI95% 0.82-0.96, p=0.005), statins HR 0.90 (CI95% 0.84-0.96, p=0.003), diuretics HR 1.48 (CI95% 1.38-1.59, p<0.001), anticoagulant HR 1.32 (CI95% 1.20-1.47, p<0.001), antiplatelets HR 1.16 (CI95% 1.08-1.25, p<0.001) and age HR 1.1 (CI95% 1.06-1.07, p<0.001).

Discussion

This study brings results that reperfusion therapy seems to benefit women and men differently. We observed the following key findings: 1) IVT modifies the long-term survival expected in the natural course after AIS (Figure 6). 2) Women were significantly older in the group treated with medical therapy alone, but their survival was better than that of men over 80 years-old. 3) Some medications/drugs could be associated with a bad prognosis, and their use could be an indicator of that prognosis. 4) Women in the group of EVT with or without IVT showed better survival than men although our sample size was not sufficient to permit robust assessments. There is much strength to this large dataset and this paper tries to address long term outcomes after reperfusion with reference to sex, type of reperfusion therapy and other cardiovascular treatments.

Some authors [18] have suggested that these differences are multifactorial, but new data suggest that there are biological differences [19]. The challenge is whether these data can achieve better health outcomes through the selection of patients with a more favorable risk versus selection on the basis of reperfusion profile.

A greater understanding of the differences and similarities between males and females with respect to previous cardiovascular risk factors [1,17,18,20], previous physical or mental condition [21,22], response to acute stroke therapies, and recovery will hopefully lead to better outcomes in both sexes in the future.

The chronic cardiovascular medications used confirm epidemiological data of stroke-related risk factors and comorbid conditions in Catalonia [4], highlighting that a higher percentage of men have been treated with antiplatelets (p=0.006), statins (p=0.001) and antidiabetics (p=0.002), apparently for more ischaemic comorbidities; and a higher percentage of women took AII-RA (p=0.026) and diuretics (p<0.001) possibly indicating a higher proportion of heart failure in that population. Possibly, the increase of mortality that is associated with cardiovascular pharmacotherapy is actually related to the basal comorbidities treated as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart failure, coronary artery diseases and/or atrial fibrillation. These comorbidities must be evaluated to determine their effects on the reperfusion therapy outcome and whether they should be included as factors in the decision to reperfusion [23].

The protective effects of statins and ARA-II are clearly independent of treatment with reperfusion therapy or the absence thereof. Statin use is widely delivered in patients who have previously suffered a stroke and were significantly more likely to survive compared with non-users [24,25]. Aspirin given together with a thrombolytic agent may worsen the risk-to-benefit ratio [26] probably due to cerebral hemorrhagic complications, but this problem was not investigated in our study. The anticoagulant treatment often has poor quality results and has been associated with high frequency of complications and poor outcome, but in selected NOAC treated patients with an acute stroke, endovascular thrombectomy is preferred if indicated and possible[27]. The use of antidiabetics was associated with higher survival in the group I, differing with results [1] that showed higher death rates among women, and higher long-term mortality in patients with diabetes [28]. Although diabetes is not a contraindication for thrombolysis therapy, patients with diabetes are often undertreated [29] and could have a sampling bias.

Previous clinical trials have largely ignored the potential for sex-specific responses to treatments [30,31]. It may be that the beneficial impact of reperfusion therapy could be neutralized by basal comorbidities and/or their treatment, or perhaps the mortality outcome of the reperfusion therapy depends more on the comorbidities profile. The development of computerized decision tools [32,33] that examine factors such as age, sex, cardiovascular comorbidities and their treatment may support the optimization of decision making to further improve EVT effectiveness as standard care for eligible patients [34] and seamlessly support different approaches to decision-making about reperfusion therapy. Eventually, the results of controlled trials [2,35-38] have confirmed the safety and efficacy of EVT and its importance for the advancement of stroke care [39], but have not been evaluated different effects by sex and comorbidities.

There are some limitations to our study. It is a large but limited observational registry and putting these all together into one analysis can make it difficult to minimizing the possible bias that exists in non randomized data, but primary randomization of sex is not possible, as sex is a nature-determined factor. Our results were limited to patients treated with reperfusion therapy and drugs for management of chronic conditions. The accessibility to procedure includes variations between different areas, and the type and quality of revascularization that patients can access often will depend on where they live particularly in the rural and remote areas.

Conclusion

Men and women have different prognoses after revascularization treatment for acute ischemic stroke. Under 80 year-old the women appear to have a better outcome than men when treated with thrombolysis therapy and/or catheter-based thrombectomy and with medical therapy alone. The men appear to have a better outcome than women when received intravenous thrombolysis. The chronic cardiovascular pharmacotherapy must be evaluated to determine their effects on the reperfusion therapy outcome and whether they should be included as factors in the decision to reperfusion.

Compliance with ethical standards

The study have been approved by the appropriate institutional and/or national research ethics committee and have been performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Ethics approval was granted by the Ethics Committee at the Research Institute of Primary Care Jordi Gol i Gurina (IDIAP), Health Department, Generalitat de Cataluña, code code 4R17/017.

Registry information was collected from the government-run healthcare provider responsible for all inpatient care in the county without contact with participants in order to gather data from the study. Identifying details of the records were excluded to achieve a complete anonymity. For this type of study formal consent is not required. This cohort study is based on AIS patients identified from the Minimum Basic Data Register at hospital discharge (CMBD-HA) through specific ICD-9 diagnostic and procedure codes. The study protocol is available at Long survival after ischemic stroke and thrombolysis in Catalonia, ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT03247036.

The authors wish to thank the research group Ebrictus for providing assistance and support to this manuscript; as well This study has been made using the “Programa public d’Analítica de Dades per a la Recerca I la Innovació en Salut a Catalunya – PADRIS by Carles Rubies I Feijoo for his technical support from AquAS (Agència de Qualitat I Avaluació Sanitàries de Catalunya).

Availability of data and material

Currently the datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. All data generated or analyzed during this study will be included in ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT03247036 after completing their validation. Competing interests: “The authors declare that they have no competing interests”

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author’s contributions

All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript. Consent to submit has been received explicitly from all co-authors, as well as from the responsible authorities at the institute/organization where the work has been carried out. Authors whose names appear on the submission have contributed sufficiently to the scientific work and therefore share collective responsibility and accountability for the results.

JC-E: has made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and involved in drafting the manuscript, revising it critically for important intellectual content, and giving final approval of the version to be published ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

SA: has made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and involved in drafting the manuscript, revising it critically for important intellectual content, and giving final approval of the version to be published ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

MQ-T has made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and involved in drafting the manuscript.

MG-H: has made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content; or analysis and interpretation of data; given final approval of the version to be published.

EM-S: has made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and involved in drafting the manuscript, and revising it critically for important intellectual content.

JB-O: has made substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and involved in drafting the manuscript, and revising it critically for important intellectual content.

VG-G: has made substantial contributions to conception and design and interpretation of data giving final approval of the version to be published and ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved and giving final approval of the version to be published.

- Eriksson M, Carlberg B, Eliasson M (2012) The Disparity in Long-Term Survival after a First Stroke in Patients with and without Diabetes Persists: The Northern Sweden MONICA Study. Cerebrovasc Dis 34: 153-160. Link: https://goo.gl/8gsVHm

- Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, de Miquel MA, Molina CA, et al. (2015) Thrombectomy within 8 Hours after Symptom Onset in Ischemic Stroke. N Engl J Med 372: 2296-2306. Link: https://goo.gl/1jKajD

- Clua-Espuny JL, Ripolles-Vicente R, Forcadell-Arenas T, Gil-Guillen VF, Queralt-Tomas ML, et al. (2015) Sex Differences in Long-Term Survival after a First Stroke with Intravenous Thrombolysis: Ebrictus Study. Cerebrovasc Dis Extra 5: 95-102. Link: https://goo.gl/bzLqsB

- Audit Clínic de l’Ictus (2015) Catalunya Pla Director de la omputer vascular cerebral. Sistema OnLine d’Informació de l’Ictusaguti Teleictus. Catalunya 2014. Link: https://goo.gl/WbvZgC

- Eriksson M, Glader EL, Norrving B, Terént A, Stegmayr B (2009) Sex Differences in Stroke Care and Outcome in the Swedish National Quality Register for Stroke Care. Stroke 40: 909-914. Link: https://goo.gl/5wqfGL

- Förster A, Gass A, Kern R, Wolf ME, Ottomeyer C, et al. (2009) Gender Differences in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Etiology, Stroke Patterns and Response to Thrombolysis. Stroke. 2009; 40: 2428-2432. Link: https://goo.gl/ABwLUU

- Lorenzano S, Ahmed N, Falcou A, Mikulik R, Tatlisumak T, et al. (2013) Does Sex Influence the Response to Intravenous Thrombolysis in Ischemic Stroke? Stroke 44: 340-3406. Link: https://goo.gl/U5GHD2

- Gargano JW, Reeves MJ; Paul Coverdell National Acute Stroke Registry Michigan Prototype Investigators (2007) Sex differences in stroke recovery and stroke-specific quality of life: Results from a statewide stroke registry. Stroke 38: 2541-2548. Link: https://goo.gl/ahs3JZ

- Niewada M, Kobayashi A, Sandercock PA, Kaminski B, Czlonkowska A (2005) Influence of gender on baseline features and clinical outcomes among 17,370 patients with confirmed ischaemic stroke in the international stroke trial. Neuroepidemiology 24: 123-128. Link: https://goo.gl/uvfT5z

- Kent DM, Buchan AM, Hill MD (2008) The gender effect in stroke thrombolysis. Of CASES, controls, and treatment-effect modification. Neurology 71: 1080-1083. Link: https://goo.gl/CbpTkP

- Meseguer E, Mazighi M, Labreuche J, Arnaiz C, Cabrejo L, et al. (2009) Outcomes of Intravenous Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator Therapy According to Gender. A Clinical Registry Study and Systematic Review. Stroke 40: 2004-2010. Link: https://goo.gl/1NjMhd

- Clua-Espuny JL, Ripolles-Vicente R, Lopez-Pablo C, Panisello-Tafalla A, et al. (2015) Diferenciasen la supervivencia después de un episodio de ictus tratado con fibrinólisis. Estudio Ebrictus. Aten Primaria 47: 108-116. Link: https://goo.gl/ZSNSvx

- Buijs JE, Uyttenboogaart M, Brouns R, de Keyser J, Kamphuisen PW, et al. (2016) The Effect of Age and Sex on Clinical Outcome after Intravenous Recombinant Tissue Plasminogen Activator Treatment in Patients with Acute Ischemic Stroke. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 25: 312-316. Link: https://goo.gl/1bDVMD

- Phan HT, Blizzard CL, Reeves MJ, Thrift AG, Cadilhac D, et al. (2017) Sex Differences in Long-Term Mortality After Stroke in the INSTRUCT (INternational STRoke oUtComes sTudy): A Meta-Analysis of Individual Participant Data. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 10: pii: e003436. Link: https://goo.gl/AF5zkY

- Clua-Espuny JL, Piñol-Moreso JL, Panisello-Tafalla A, Lucas-Noll J, Gil-Guillen VF, et al. (2012) Estudio Ebrictus. Resultados funcionales, supervivencia y años potenciales de vida perdidos después del primer episodio de ictus. Aten Primaria 44: 223-231. Link: https://goo.gl/GZURvw

- Clua-Espuny JL, Piñol-Moreso JL, Gil-Guillén JF, Orozco-Beltran D, Panisello-Tafalla A, et al. (2012) La atención sanitaria del ictus en el áreaTerres de l’Ebre desde la implantación del Código Ictus: Estudio Ebrictus. Med Clín 138: 609-611. Link: https://goo.gl/Q5gSRn

- Clua-Espuny JL, Garcés-Redondo M, Lucas-Noll J, Panisello-Tafalla A, Queralt-Tomas ML (2014) Stroke Epidemiology, Survival and Disability in A Mediterranean Population According Malmgren’s Criteria. Ebrictus Cohort. Ann Vasc Med Res 1: 1004. Link: https://goo.gl/Z6XWCo

- Mehndiratta P, Wasay M, Mehndiratta MM (2015) Implications of Female Sex on Stroke Risk Factors, Care, Outcome and Rehabilitation: An Asian Perspective. Cerebrovasc Dis 39: 302-308. Link: https://goo.gl/G9CVr8

- Hametner C, Ringleb P, Kellert L (2015) Sex and Hemisphere – A Neglected, Nature-Determined Relationship in Acute Ischemic Stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 40: 59-66. Link: https://goo.gl/3rha8A

- Queralt-Tomas ML, Panisello-Tafalla A, González-Henares A, Clua-Espuny JL, Campo-Tamayo W, et al. (2017) Complex Chronic Patients and Atrial Fibrillation: Association with Cognitive Deterioration and Heart Failure. J Clin Exp Res Cardiol 3: 104. Link: https://goo.gl/rRJhCD

- Zupanic E, von Euler M, Kåreholt I, Escamez BC, Fastbom J, Norrving B, et al. (2017) Thrombolysis in acute ischemic stroke in patients with dementia. A Swedish registry study. Neurology 89: 1860-1868. Link: https://goo.gl/QEnKQg

- Clua-Espuny JL, González-Henares MA, Queralt-Tomas ML, Campo-Tamayo W, Muria-Subirats E, et al. (2017) Mortality and Cardiovascular Complications in Older Complex Chronic Patients with Type 2 Diabetes. Biomed Res Int 2017: 6078498: 6. Link: https://goo.gl/Z8tpwc

- Van der Berg SA, Mulder MJHL, Goldhoorn RB, Coutinho JM, Roozenbeek B, et al. (2018) Blood pressure and functional outcome after endovascular treatment: Results from the MR CLEAN Registry. Large Clinical Trials 2. 4th European Stroke Organisation Conference, 16-18 May 2018/ Gothenburg, Sweden. Link: https://goo.gl/HsT7JK

- Ishikawa H, Wakisaka Y, Matsuo R, Makihara N, Hata J, et al. (2016) Influence of Statin Pretreatment on Initial Neurological Severity and Short-Term Functional Outcome in Acute Ischemic Stroke Patients: The Fukuoka Stroke Registry. Cerebrovasc Dis 42: 395-403. Link: https://goo.gl/MtNdwx

- Aboa-Eboulé C, Binquet C, Jacquin A, Hervieu M, Bonithon-Kopp C, et al. (2012) Effect of previous statin therapy on severity and outcome in ischemic stroke patients: a population-based study. J Neurol 260: 30-37. Link: https://goo.gl/k1nd8Q

- Ciccone A, Motto C, Aritzu E, Piana A, Candelise L (2000) Negative Interaction of Aspirin and Streptokinase in Acute Ischemic Stroke: Further Analysis of the Multicenter Acute Stroke Trial-Italy. Cerebrovasc Dis 10: 61-64. Link: https://goo.gl/LjUahQ

- Steffel J, Heidbuchel H (2018) ‘Ten Commandments’ of the EHRA Guide for the Use of NOACs in AF. Eur Heart J 39: 1322–1329. Link: https://goo.gl/mfoJmT

- Nikneshan D, Raptis R, Pongmoragot J, Zhou L, Johnston SC, Saposnik G, et al. (2013) Predicting Clinical Outcomes and Response to Thrombolysis in Acute Stroke Patients With Diabetes. Diabetes Care 36: 2041-2047. Link: https://goo.gl/p6V2Y5

- Reeves MJ1, Vaidya RS, Fonarow GC, Liang L, Smith EE, et al. (2010) Get with the Guidelines Steering Committee and Hospitals. Quality of care and outcomes in patients with diabetes hospitalized with ischemic stroke: findings from Get with the Guidelines-Stroke. Stroke 41: e409-e417. Link: https://goo.gl/yUBmjT

- Simpson CR, Wilson C, Hannaford PC, Williams D (2005) Evidence for age and sex differences in the secondary prevention of stroke in Scottish primary care. Stroke 36: 1771-1775. Link: https://goo.gl/oQngWK

- Ankolekar S, Rewell S, Howells DW, Bath PMW (2012) The Influence of Stroke Risk Factors and Comorbidities on Assessment of Stroke Therapies in Humans and Animals. Int J Stroke 7: 386-397. Link: https://goo.gl/E772S2

- Flynn D, Nesbitt DJ, Ford GA, McMeekin P, Rodgers H, et al. (2015) Development of a computerized decision aid for thrombolysis in acute stroke care. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 15: 6. Link: https://goo.gl/esVENy

- Khatri P, Hacke W, Fiehler J, Saver JL, Diener HC, et al. (2015) State of Acute Endovascular Therapy: Report From the 12th Thrombolysis, Thrombectomy, and Acute Stroke Therapy Conference. Stroke 46: 1727-1734. Link: https://goo.gl/ZraajJ

- Alberts MJ, Ollenschleger MD, Nouh A (2018) DAWN of a New Era for Stroke Treatment: Implications of the DAWN Study for Acute Stroke Care and Stroke Systems of Care. Circulation 137: 1767-1769. Link: https://goo.gl/mM4rFE

- Campbel BCV, Mitchell PJ, Kleinig TJ, Dewey HM, Churilov L, et al. (2015) Endovascular Therapy for Ischemic Stroke with Perfusion-Imaging Selection. N Engl J Med 372: 1009-1018. Link: https://goo.gl/M9Bb7L

- Goyal M, Demchuk AM, Menon BK, Eesa M, Rempel JL, et al. (2015) for the ESCAPE Trial Investigators Randomized Assessment of Rapid Endovascular Treatment of Ischemic Stroke. N Engl J Med 372: 1019-1030. Link: https://goo.gl/AVR7Ge

- Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, Diener HC, Levy EI, et al. (2015) for the SWIFT PRIME Investigators. Stent-Retriever Thrombectomy after Intravenous t-PA vs. t-PA Alone in Stroke. N Engl J Med 372: 2285-2295. Link: https://goo.gl/9mQjks

- de Sousa DA, von Martial R, Abilleira S, Gattringer T, Kobayashi A, et al. (2018) Access to and delivery of acute ischaemic stroke treatments: A survey of national scientific societies and stroke experts in 44 European countries. European Stroke Journal 0: 1-16. Link: https://goo.gl/jx8nys

- The burden of Stroke in Europe report (2017). King’s College London for the Stroke Alliance for Europe (SAFE). Brussels, May 11th 2017. Link: https://goo.gl/JsL5t1

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley