Open Journal of Pharmacology and Pharmacotherapeutics

Label Comprehension of a Prototype Household Antibiotic Kit for Emergency use in Anthrax Bioterror Preparedness

1Pharmaron Clinical Pharmacology Center (CPC), Baltimore, Maryland, USA

2University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA

Author and article information

Cite this as

Al-Ibrahim M, et al. Label Comprehension of a Prototype Household Antibiotic Kit for Emergency use in Anthrax Bioterror Preparedness. Open J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2026; 11(1): 001-007. Available from: 10.17352/ojpp.000028

Copyright License

© 2026 Al-Ibrahim M, et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Background: In 2001, powdered spores of Bacillus anthracis were used for bioterrorism attacks in several U.S. cities. In response, the U.S. government implemented a strategic national stockpile strategy and experimented with household antibiotic kits (HAKs) for emergency use. However, regulatory approval for public distribution of HAKs was not implemented due to concerns about misuse and potential adverse health effects.

Objective: This study assessed comprehension of key HAK labeling messages, including indication, dosage, contraindications, warnings, and overall safe use of HAK contents among the general population and first responders. The influence of literacy and socio-economic variables on comprehension of the labels was also evaluated.

Study design: This prospective, open-label, cross-sectional pilot study assessed the comprehension of key HAK labeling messages through one-on-one interviews using a pre-tested questionnaire. Adults from the general population and first responders in Maryland were recruited for the study; highly trained health professionals such as doctors, pharmacists, and nurses were excluded. Participants’ health literacy was stratified using the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) tool.

Results: At least 80% of participants from the general population, and a higher proportion of first responders, correctly answered 80% or more of the pre-tested questionnaire. Participants with a REALM-equivalent literacy level of 7th grade or above demonstrated significantly higher comprehension across all categories of HAK labeling, while a literacy level of 6th grade or below was a strong predictor of inadequate comprehension.

Conclusion: Comprehension levels of 80% or higher for correct HAK use are comparable to or exceed those for standard prescription medications, supporting its potential approval for public distribution as an anthrax preparedness measure. However, observed lower comprehension of rates in those with a REALM score sixth grade or below emphasizes the need for further improvement for HAK labeling and additional interventions to ensure safe and effective use across all demographics.

Bacillus anthracis (B. anthracis) is the bacterium responsible for three forms of Anthrax disease: inhalational, cutaneous, or gastrointestinal. Inhalational anthrax is the most lethal form, with a rapid progression and a modern age fatality rate exceeding 50% [1,2]. This pathogen can remain dormant for an extended period by forming a resilient protective layer (anthrax spores) and quickly becomes infectious when conditions permit. Since the mid-1990s, B. anthracis has been considered a likely agent of biological warfare or terrorism due to its spore-forming ability, environmental resilience, potent virulence factors, and ease of deliberate dissemination [3,4]. In 2001, the United States experienced a bioterrorism attack with dried anthrax spores spread via mailed letters and packages affecting people from the District of Columbia, Florida, New Jersey, and New York. These attacks caused 22 cases, including 10 inhalational and 12 cutaneous, resulting in five deaths. Despite treatment with multi-drug antibiotic regimens and intensive supportive care, the fatality rate was 40% in inhalational cases [5,6].

In 1970, the World Health Organization estimated that a bioterror attack involving aerosolized anthrax in a population of 5 million could result in 250,000 casualties, including up to 100,000 deaths. The US Office of Technology Assessment also projected that releasing 100 kilograms of anthrax over Washington, D.C., could cause 130,000 to 3 million deaths. The CDC estimated the economic cost of such an attack at $26.2 billion per 100,000 people exposed [4,7,8].

The disease outcomes and severity from exposure to B. anthracis can be prevented or mitigated effectively by immediate prophylactic antibiotic treatment given within 24-48 hours of exposure. During the 2001 anthrax attacks, approximately 10,000 individuals with potential exposures were advised to initiate prophylactic antibiotic therapy, and no cases of inhalation anthrax were reported among them [9,10]. Since 2001, the US government has made progress in preparation for a potential repeat anthrax attack, and this success with prophylactic antibiotic therapy was a critical consideration in planning a national preparedness strategy. As such, a Strategic National Stockpile (SNS) has been created, storing 60-day antibiotic regimens to provide treatment for 40 million individuals exposed to inhalation anthrax. The aim was to establish a country-wide network of warehouses capable of delivering supplies to any location within 12-24 hours of a federal decision to activate mass distribution [11]. To deliver these countermeasures rapidly during a large-scale anthrax event five modalities have been proposed (i) classical points-of-dispensing (PODs) operated by local governments with federal stockpile support; (ii) residential delivery of antibiotics via the U.S. Postal Service under Executive Order 13527, with National Postal Model (NPM) volunteers pre-issued Household Antibiotic Kits (HAKs) under Emergency Use Authorization (EUA); (iii) community-based pharmaceutical caches pre-positioned in healthcare institutions to enable rapid deployment; (iv) pre-event dispensing of medicines to first responders to ensure readiness; and (v) pre-event household placement of medical kits containing essential prescription drugs, to be used only under public health direction [12].

HAK packages include labels intended to guide the general population in the proper and timely use of antibiotics during emergencies. However, pre-positioning of HAKs in homes carries a risk of misuse in the absence of supervision by a healthcare professional [13]. The appropriate use of the antibiotics provided in the HAK depends primarily on an individual’s ability to follow instructions contained in the package. Almost half of American adults have difficulty understanding health-related information, medication instructions, and common symbols or text on drug warning labels. This is more prevalent among those with low literacy levels and the elderly, leading to the misuse of prescription medications and increased risk of adverse drug events [11,14-20]. The Institute of Medicine (IOM), considering the potential risks of HAK misuse, did not recommend the development of an FDA-approved HAK unless it could be demonstrated that the likelihood of inappropriate use is comparable to that observed with standard prescription medications [11,21].

To address these concerns, the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) initiated this pilot study to evaluate the comprehension levels of a prototype HAK in English-speaking adults, with particular attention to individuals with low literacy.

The primary objective of this study was to assess comprehension of HAK instructions among the general population. A second cohort of first responders was also included, as they have an essential role in pre-event dispensing. Participants’ understanding of key labeling messages, including indication, dosage, and dosing interval, contraindications, and antibiotic-related warnings, as well as broader concepts of safe and appropriate use, such as storage, child safety, and administration methods were evaluated. In addition to literacy level, other factors, including age and other demographics, were analyzed. Findings were intended to inform policy decisions, improve label clarity, and therefore enhance preparedness for a future anthrax bioterrorism event.

Materials and methods

Study design

This was a prospective, open-label, cross-sectional study to assess the comprehension of the key communication messages from the labels and instructions in the HAK. This medical kit was modeled after the original HAK used in the Emergency Use Authorization granted by the FDA to the U.S. Postal Service (USPS EUA) [22]. While it contained a similar labelled dummy doxycycline bottle, two documents were added to the HAK used in this study: a Fact Sheet, and instructions for emergency mixing of doxycycline hyclate with food for children and adults who cannot swallow pills; these were modified from the USPS EUA versions [22].

The study was conducted in two phases. In Phase1, the draft questionnaire was evaluated by focus group interviews and modified accordingly for ease of use and understandability. In brief, the draft questionnaire was developed in accordance with FDA guidance for label comprehension studies [23] and refined through focus group interviews to ensure clarity and usability. This questionnaire contained 25 open- and closed-ended questions (Q) assessing comprehension of key HAK label information: (i) valid reasons for medication use (Indication: Q1-5), (ii) recommended dose and intervals (Dose and Dosing Interval): Q #6-10, #21-25) (iii) medical reasons to avoid use of the medication (Contraindications; Q11–13, 15–17), (iv) potential serious risks and safety hazards (Warnings; Q #11–14, 18, 20) and (v) overall comprehension for safe and appropriate use of the drug (Q1–25). Literacy experts from the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy evaluated the questionnaire for clarity, usability, and appropriateness in three focus groups of 6–8 participants each, stratified by literacy levels [24]. Following iterative revisions, the optimized questionnaire received Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

In Phase 2, the optimized IRB-approved questionnaire was used as a standardized script to assess each participant’s comprehension of the key messages conveyed by the HAK labels and instructions, through one-on-one interviews conducted by trained research associates. During the interviews, participants were provided with a complete HAK, which included a plastic bag with an outer pocket, a sample doxycycline bottle, the HAK fact sheet, mixing instructions, a MedWatch Form 3500 cover sheet [25], and a 10 mL oral syringe. Participants were allowed time to examine the HAK contents and refer to the materials when answering the questions. Participants were instructed to circle their responses from the provided answer choices. At the end of the interview, participants were invited to offer suggestions for improving the readability and comprehensibility of the materials and submit additional comments.

Study population

A total of 600 adult male and female current residents of Maryland, aged 18 years and older, who can read and understand English, were enrolled in the study after informed consent. Among them were a cohort of 106 first responders, including police officers, firefighters, and emergency medical technicians (Table 1). Individuals with visual impairments, who had received prior disaster preparedness training (except first responders), and healthcare professionals (e.g., physicians, registered nurses, physician assistants, or dentists) were excluded from the study. To ensure representation across age groups, ethnic, racial, cultural, and literacy backgrounds, including individuals with lower literacy levels, participants were recruited from communities across the State of Maryland (Table 1).

Literacy level assessment

The participant’s literacy level was assessed using the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM), which measures the individual’s ability to recognize and pronounce 66 medical terms of varying complexity [24]. Each participant was assigned a grade-equivalent reading level based on the number of words they read and pronounced correctly, placing them into one of three categories: i) below 6th grade, ii) 7th – 8th grade, or iii) high school and above.

Endpoint data analysis and statistics

The primary endpoint was the proportion of participants who demonstrated satisfactory comprehension of the HAK labels, defined as correctly answering at least 80% of the questionnaire items assessing the key communication messages. Multiple regression and cluster analyses were performed to identify significant patterns of comprehension across different subgroups of the study population. The Chi-square or appropriate t-test was applied to compare between two groups.

Results

In this study, the general population (N = 494) and first responders (N = 106) represented 82% and 18% of the total 600 participants, respectively (Table 1). Compared with the general population, the first responder cohort was predominantly male, Caucasian, and suburban, with higher household income, full-time employment, and higher educational attainment, including college education (p < 0.0001 for all variables, Table 1). A majority (93.5%) of the participants demonstrated a literacy level equivalent or above 7th-grade level (high grades; REALM score 45-66), while 7.9% of the general study participants (39 out of 494) had literacy grade equivalent to 6th grade or lower (low grade; REALM score 0-44) (Table 1).

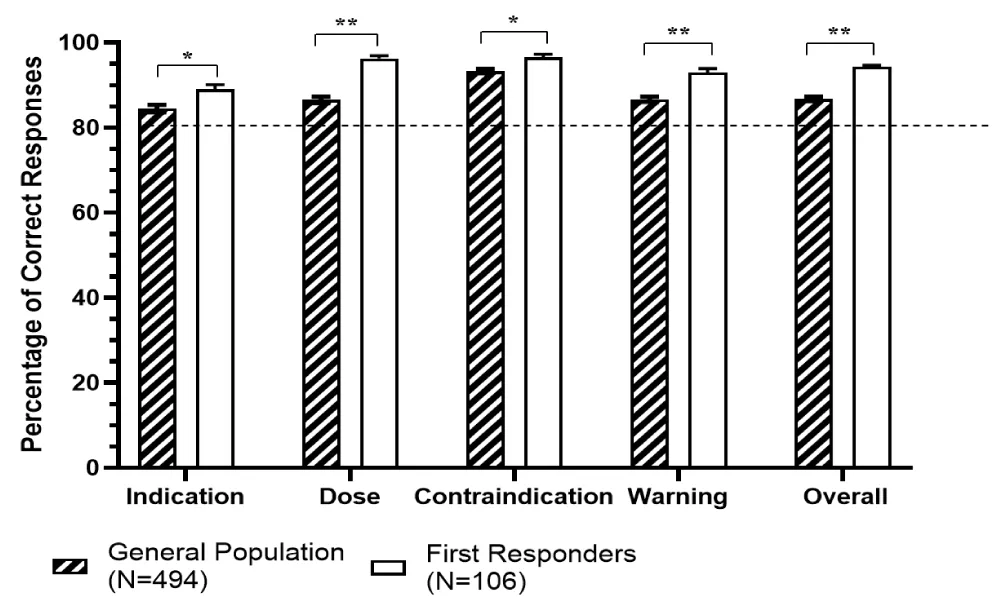

The questionnaire was designed to assess the comprehension of HAK labels by measuring the correct responses to each of the sets of questions aimed at four key messages among the participants. The net scoring averages calculated from the percentage of correct responses among both the general population, and first responders were 84.5% or higher (Figure 1). As expected, when compared with the general population, first responders demonstrated significantly higher comprehension across key message categories, including Indication (p = 0.0006), Dose and Dosing Interval (p < 0.001), and Warnings (p < 0.0001), as well as Overall comprehension for safe and appropriate use of the drug (p = 0.0001; Figure 1). More than 80% of the participants in general population and a significantly higher percentage of participants in first responders correctly answered 80% of the questions for each of the four key messages, as well as for overall comprehension of the HAK label (Table 2).

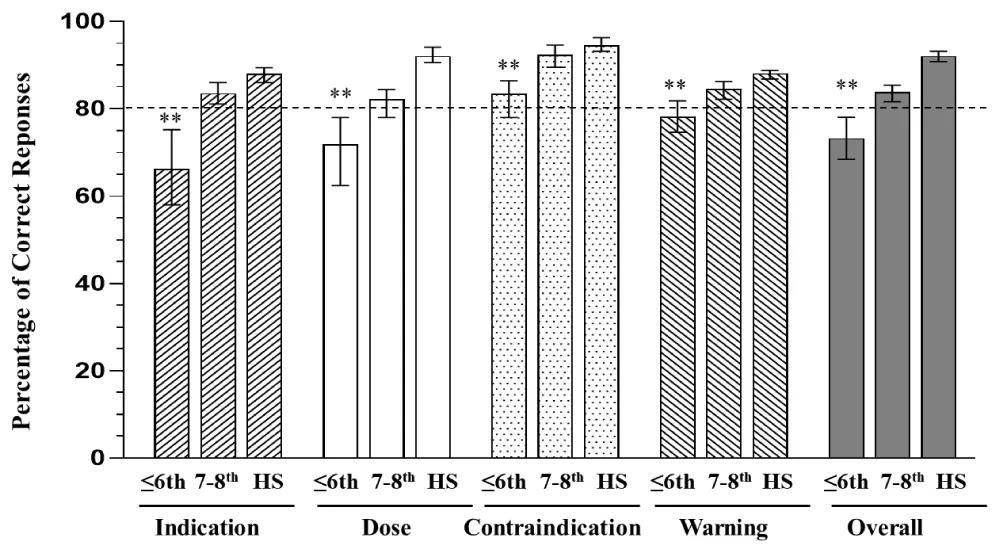

Comprehension rates for each of the four key messages and overall comprehension, for the safe and appropriate use of the drug (as described above) were further analyzed according to literacy grade equivalents among all the participants (Figure 2). Literacy level of all the participants was assessed using the REALM instrument (Methods; Table 1) and categorized into three groups: ≤ 6th grade, 7th – 8th grade, and ≥ high school. Participants in the higher literacy groups (7th – 8th grade and ≥ high school) correctly answered ≥ 80% of the respective questions assessing understanding of Indication, Dose/Dosing Interval, Contraindications, Warnings, and Overall comprehension on safe and appropriate use of the drug. In contrast, participants with ≤ 6th literacy grade scored below 80% across all categories except for Contraindications (Figure 2). The average comprehension scores across all key messages including contradictions and overall comprehension on safe and appropriate use of the drug assessment, were significantly lower (p < 0.0001) among participants with ≤ 6th grade literacy compared with those in the 7th – 8th grade or ≥ high school groups (Figure 2). In addition, for all four primary and overall comprehension, the lower limit of the 95% CI fell below 80% for the 6th grade and below level (Figure 2).

Discussion

Inhalational anthrax remains a major concern of public health agencies in a bioterrorism emergency. In 2023, the FDA approved a newer adjuvanted version of the anthrax vaccine (Cyfendus AVA, adjuvanted) [26]. However, this requires two intramuscular doses given two weeks apart in conjunction with antibiotics. This vaccine is not recommended for children or pregnant women. Anthrax immune globulin is another addition to the anthrax treatment armamentarium, but is not a preventive measure and is recommended for the treatment of inhalational anthrax in a critical care setting [27].

Rapid and timely distribution of FDA-approved medications to prevent clinical anthrax (e.g., doxycycline) can be achieved through direct residential delivery of HAK via pre-deployed community-based caches and pre-event dispensing to first responders. While these approaches could support an effective response during an anthrax attack, approval of the FDA for use of HAK is not available due to concerns of potential adverse outcomes resulting from the misuse of HAK [11,21]. This concern is supported by studies showing that a substantial portion of U.S. adults struggle to interpret health information [17,18]. The current pilot study was conducted to provide information to the FDA on a prototype HAK and the comprehension of its labels and proper use by the general population.

The participants representing the general population were recruited from Maryland communities. Additionally, a cohort of first responders was included in the study, as they are likely to serve as a critical resource for the pre-event distribution of HAKs and a source of information during a bioterrorism emergency. The REALM, a validated reading recognition test for identifying low health literacy [24] was used as a stratification tool to classify participants by literacy level and examine potential predictors of comprehension outcomes measured by the questionnaire. The questionnaire used to assess HAK comprehension was developed with literacy experts and pre-tested in small focus groups to ensure clarity and reliability.

Adequate comprehension of the HAK label was demonstrated by more than 80% of participants overall, including both the general population and first responder cohorts, as measured by correct responses to ≥ 80% of items addressing four primary communication domains (indications, dosing and interval, contraindications, and warnings), as well as the overall composite comprehension for safe and appropriate use of the drug core. As expected, comprehension rates were higher among first responders compared with the general population. In summary, when exposed to the medical information contained in the HAK, a majority of the general population was able to adequately understand the primary communication messages to make appropriate use of the drug. These findings are encouraging, as they suggest that concerns about potential misuse of antibiotics in HAKs due to labeling misunderstanding are no greater than those reported for commonly used prescription labels [19]. Moreover, the strong performance of first responders supports their potential role in pre-event HAK dispensing and in providing accurate guidance to the public during an anthrax bioterror emergency.

REALM grade equivalency has been validated as a key predictor of comprehension of medical information, including prescription use [24]. Consistent with previous studies, our findings showed that participants with REALM level at 6th-grade or below had lower comprehension of the HAK labeling compared with their peers at grade levels 7th or higher [28]. Analyses of socioeconomic factors further suggested that certain subpopulations experienced difficulty with understanding HAK information. However, definitive and statistically significant identification of all predictors, including age, gender, ethnic origin, cultural, work level, etc., for lower comprehension was limited by the relatively small sample size of this pilot study. Although we targeted a larger sample size at the lowest grade level, the study’s limited scope constrained the number of participants screened and overall recruitment. Only 7.9% of general population participants were at the 6th grade level or below; larger future studies can achieve greater representation of this segment of the population.

The findings from this pilot study provide information that may improve the design of future HAK models as a strategic preparedness measure against anthrax. Individuals with a 6th-grade or lower literacy level demonstrated limited comprehension of HAK materials, emphasizing the need for additional efforts to effectively communicate with these vulnerable populations. Comprehension may be improved by enhancing visual aids, such as cartoons, or incorporating audiovisual materials to clarify key messages. Nevertheless, in the event of an emergency, HAK recipients would also be exposed to supplementary governmental public health communications via television, radio, and the internet, which would reinforce instructions and promote appropriate use. Another important consideration is that HAKs contain doxycycline in tablet form; children and individuals unable to swallow pills may require crushed tablets. Given doxycycline’s bitter taste, HAK instructions should include guidance on administering crushed tablets with common household foods or beverages to improve palatability and compliance. This pilot study for anthrax preparedness was conducted following FDA guidance for label comprehension studies [23]. The methodology used here can serve as a foundation for larger-scale studies, and the observations made could inform and enhance bioterrorism preparedness strategies for other potential biological threats.

Implications for policy & practice

- The risk of misuse of HAK due to low comprehension of the label instruction, among the general population were found to be no greater than those already reported for prescription drugs.

- Limited comprehension of HAK instructions was mostly observed among those who had a medical literacy level at sixth-grade or below. Therefore, additional targeted measures, such as inclusion of graphic instructions inside the kit, simplified visuals, cartoons, or audiovisual aids, will be needed to ensure improved comprehension and safe and effective use in these vulnerable groups.

- Additionally, government communication tools, including television, radio, and internet messaging, can be utilized to promote comprehension and proper HAK use during actual emergencies.

Acknowledgement

We acknowledge the support and contributions of Dr. Robert S. Beardsley and Dr. Francoise G. Pradel of the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy; Chesapeake Health Education Program, Inc., and all participants for their cooperation and assistance.

Statements and declarations

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the United States government.

Funding and sponsor of the study: Dr. Al-Ibrahim received the funding from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Broad Spectrum Antimicrobials Program, Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority.

Financial disclosure: The authors have no relevant financial interests regarding this manuscript to disclose.

Human participants compliance statement: Ethical approval of this research was obtained from the Internal Review Board of the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

- Hendricks K, Person MK, Bradley JS, Mongkolrattanothai T, Hupert N, et al. Clinical features of patients hospitalized for all routes of anthrax, 1880–2018: a systematic review. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(Suppl):S341–S353. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciac534

- Holty JEC, Bravata DM, Liu H, Olshen RA, McDonald KM, Owens DK. Systematic review: a century of inhalational anthrax cases from 1900 to 2005. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144(4):270–280. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-144-4-200602210-00009

- Inglesby TV, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, Friedlander AM, et al. Anthrax as a biological weapon: medical and public health management. JAMA. 1999;281(18):1735–1745. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.18.1735

- Inglesby TV, O’Toole T, Henderson DA, Bartlett JG, Ascher MS, Eitzen E, et al. Anthrax as a biological weapon, 2002: updated recommendations for management. JAMA. 2002;287(17):2236–2252. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.287.17.2236

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update: investigation of bioterrorism-related anthrax and adverse events from antimicrobial prophylaxis. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:973–976. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11724150/

- Hughes JM, Gerberding JL. Anthrax bioterrorism: lessons learned and future directions. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(10):1013–1014. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid0810.020466

- Johari MR. Anthrax - biological threat in the 21st century. Malays J Med Sci. 2002;9(1):1–2. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22969310/

- Kaufmann AF, Meltzer MI, Schmid GP. The economic impact of a bioterrorist attack: are prevention and postattack intervention programs justifiable? Emerg Infect Dis. 1997;3(2):83–94. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid0302.970201

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Update: investigation of bioterrorism-related anthrax, 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:1008–1010. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11724158/

- Jefferds MD, Laserson K, Fry AM, Roy S, Hayslett J, Grummer-Strawn L, et al. Adherence to antimicrobial inhalational anthrax prophylaxis among postal workers, Washington, D.C., 2001. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(10):1138–1144. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3201/eid0810.020331

- Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats. Antibiotic resistance: implications for global health and novel intervention strategies: workshop summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2010. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK54255/

- Committee on Prepositioned Medical Countermeasures for the Public; Institute of Medicine. Current dispensing strategies for medical countermeasures for anthrax. In: Prepositioning antibiotics for anthrax. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2011. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK190045/

- Lurie N, Manolio T, Patterson AP, Collins F, Frieden T. Research as a part of public health emergency response. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1251–1255. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsb1209510

- Coleman CA, Appy S. Health literacy teaching in US medical schools, 2010. Fam Med. 2012;44:504–507. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22791536/

- Shrank W, Avorn J, Rolon C, Shekelle P. Effect of content and format of prescription drug labels on readability, understanding, and medication use: a systematic review. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:783–801. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1h582

- Webb J, Davis TC, Bernadella P, Clayman ML, Parker RM, Adler D, et al. Patient-centered approach for improving prescription drug warning labels. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;72:443–449. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.05.019

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Literacy. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2004. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK216032/

- Rudd R, Kirsch I, Yamamoto K. Literacy and health in America. Policy information report. Princeton (NJ): Educational Testing Service; 2004. 52 p. Available from: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED486416

- Wolf MS, Davis TC, Shrank W, et al. To err is human: patient misinterpretations of prescription drug label instructions. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;67:293–300. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.024

- Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, et al. Low literacy impairs comprehension of prescription drug warning labels. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:847–851. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00529.x

- Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats. Antibiotic resistance: implications for global health and novel intervention strategies: workshop summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2010. Available from: https://doi.org/10.17226/12925

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Authorization of emergency use of doxycycline hyclate tablet emergency kits for eligible United States Postal Service participants in the Cities Readiness Initiative and their household members. 2008. Available from: https://www.federalregister.gov/d/E8-25062

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Guidance for industry: label comprehension studies for nonprescription drug products. 2010. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/label-comprehension-studie…

- Davis TC, Long SW, Jackson RH, Mayeaux EJ, George RB, Murphy PW, et al. Rapid estimate of adult literacy in medicine: a shortened screening instrument. Fam Med. 1993;25:391–395. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8349060/

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). MedWatch Form FDA 3500. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/safety/medical-product-safety-information/medwatch-forms-fda-safety-reporting

- Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Products approved for anthrax: Cyfendus (anthrax vaccine adsorbed, adjuvanted). 2023. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/cyfendus

- Mytle N, Hopkins RJ, Malkevich NV, Basu S, Meister GT, Sanford DC, et al. Evaluation of intravenous anthrax immune globulin for treatment of inhalation anthrax. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57:5684–5692. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1128/aac.00458-13

- Davis TC, Wolf MS, Bass PF, Thompson JA, Tilson HH, Neuberger M, et al. Literacy and misunderstanding prescription drug labels. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:887–894. Available from: https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-145-12-200612190-00144

Article Alerts

Subscribe to our articles alerts and stay tuned.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Save to Mendeley

Save to Mendeley